How your solar rooftop became a national security issue

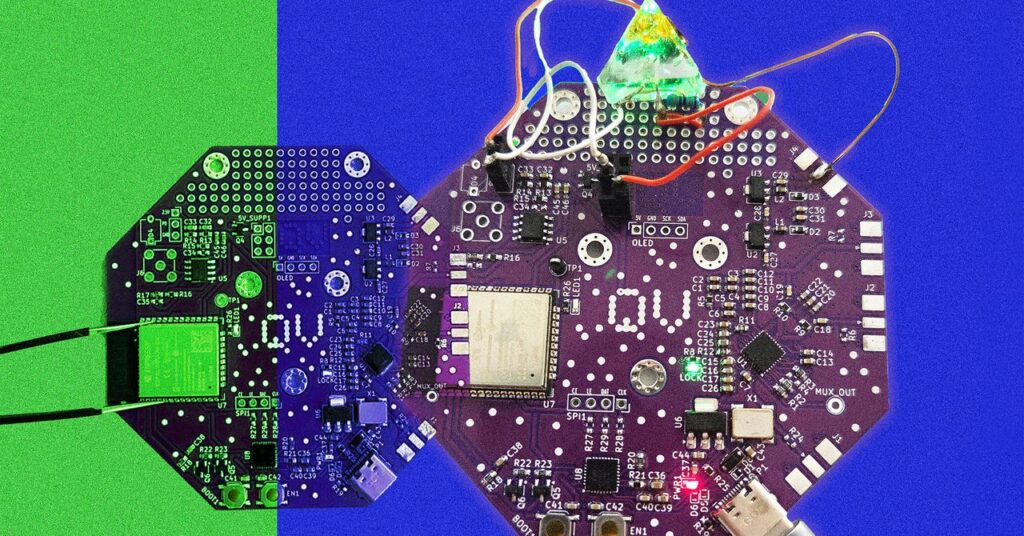

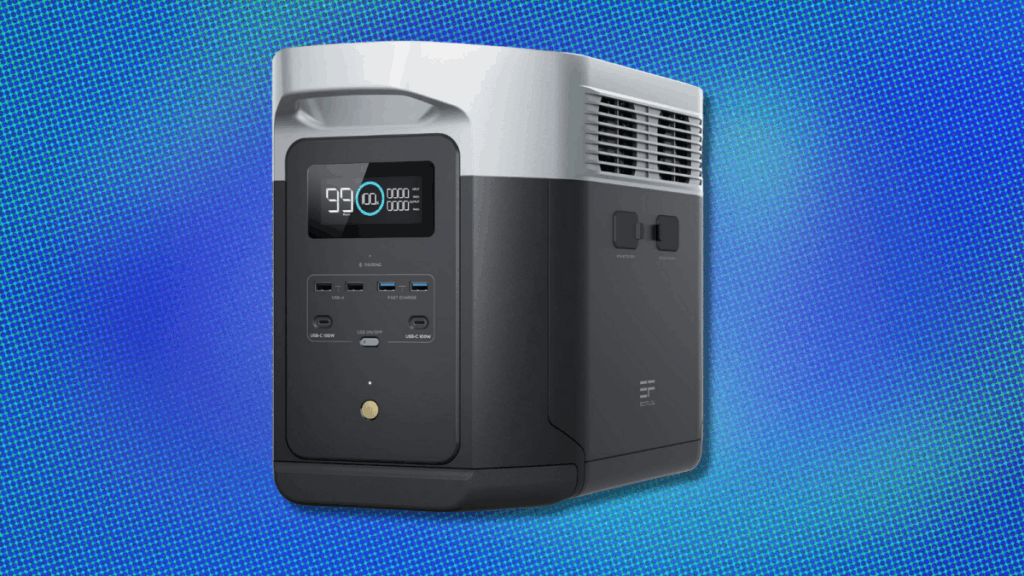

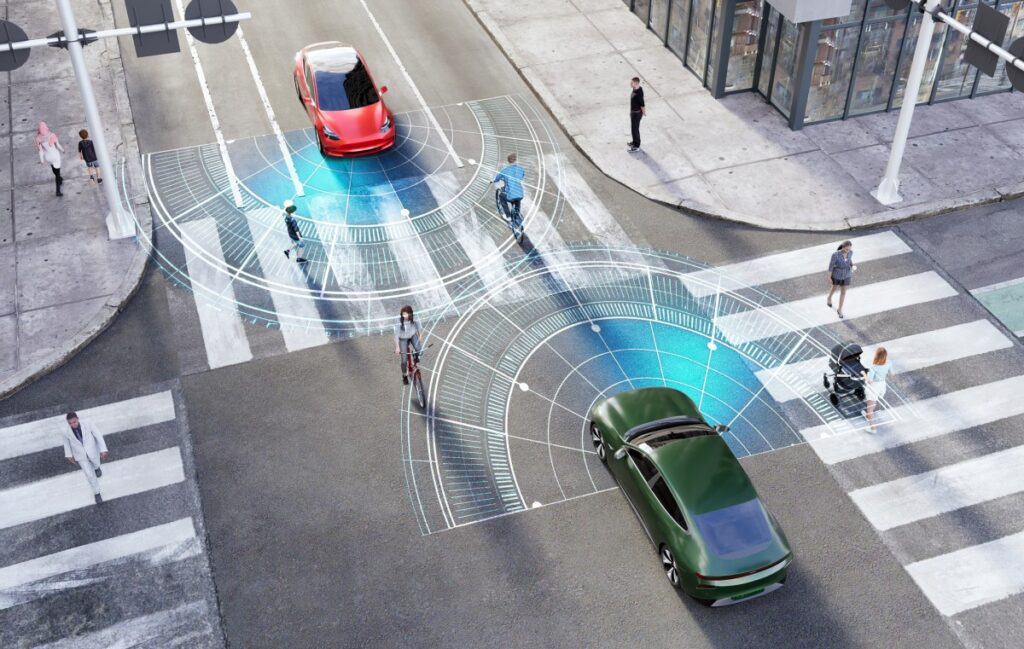

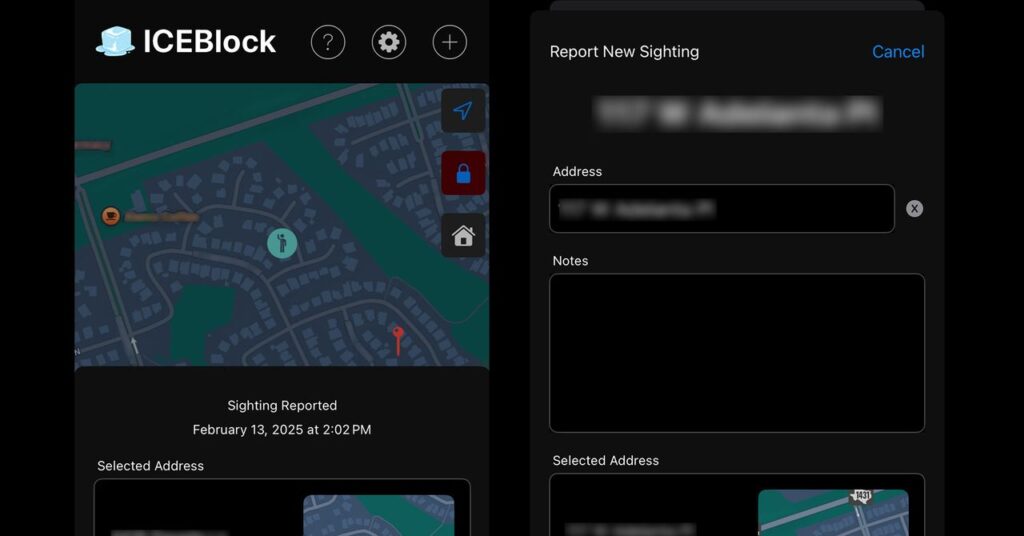

James Showalter describes a pretty specific if not entirely implausible nightmare scenario. Someone drives up to your house, cracks your Wi-Fi password, and then starts messing with the solar inverter mounted beside your garage. This unassuming gray box converts the direct current from your rooftop panels into the alternating current that powers your home.

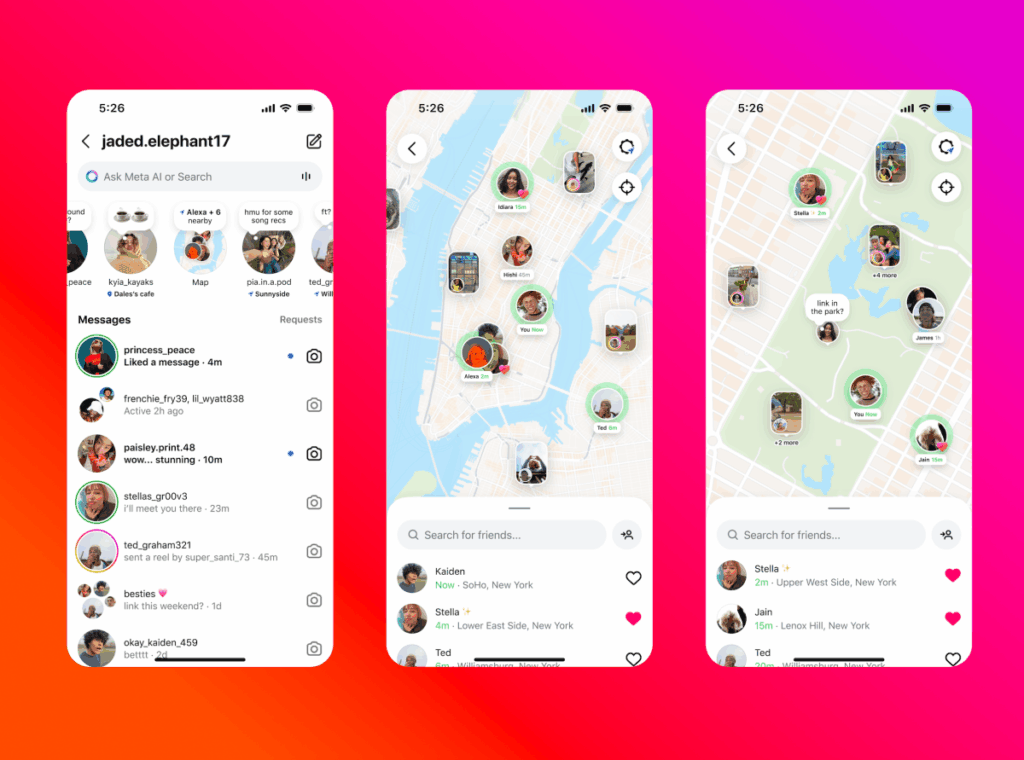

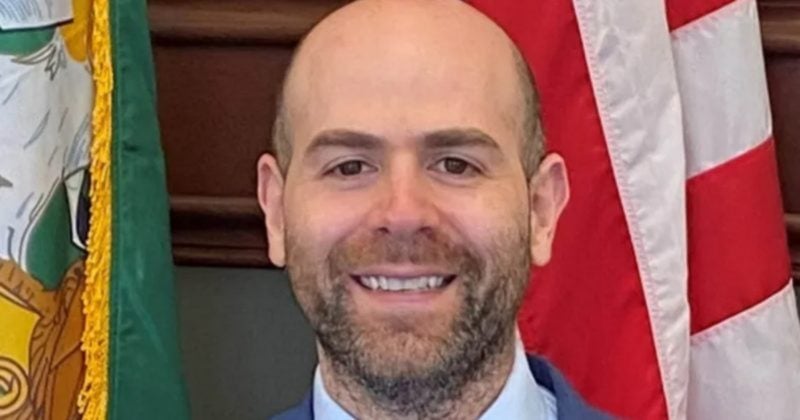

“You’ve got to have a solar stalker” for this scenario to play out, says Showalter, describing the kind of person who would need to physically show up in your driveway with both the technical know-how and the motivation to hack your home energy system.

The CEO of EG4 Electronics, a company based in Sulphur Springs, Texas, doesn’t consider this sequence of events particularly likely. Still, it’s why his company last week found itself in the spotlight when U.S. cybersecurity agency CISA published an advisory detailing security vulnerabilities in EG4’s solar inverters. The flaws, CISA noted, could allow an attacker with access to the same network as an affected inverter and its serial number to intercept data, install malicious firmware, or seize control of the system entirely.

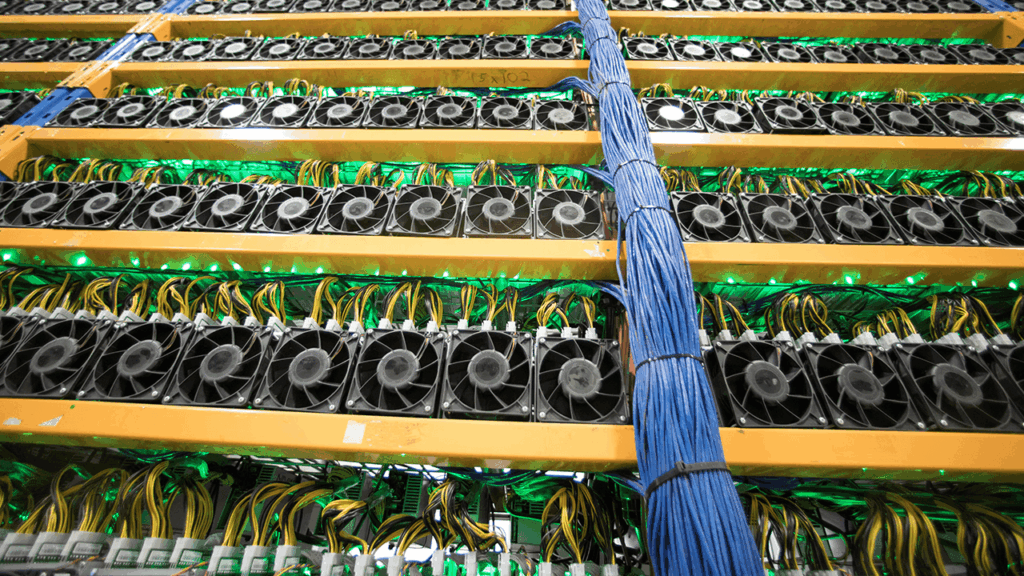

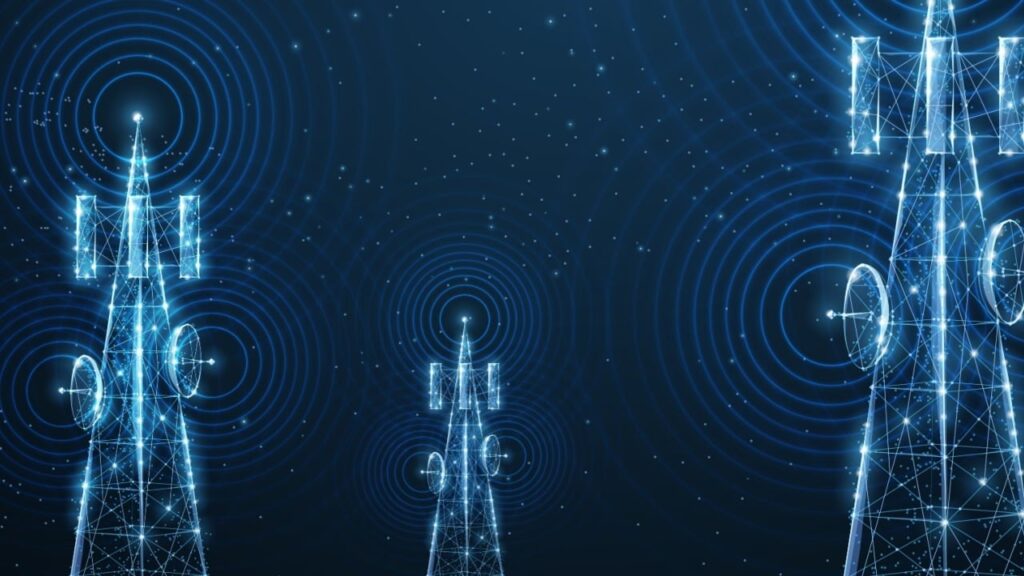

For the roughly 55,000 customers who own EG4’s affected inverter model, the episode probably felt like an unsettling introduction to a device that they little understand. What they’re learning is that modern solar inverters aren’t simple power converters anymore. They now serve as the backbone of home energy installations, monitoring performance, communicating with utility companies, and, when there’s excess power, feeding it back into the grid.

Much of this has happened without people noticing. “Nobody knew what the hell a solar inverter was five years ago,” observes Justin Pascale, a principal consultant at Dragos, a cybersecurity firm that specializes in industrial systems. “Now we’re talking about it at the national and international level.”

Security shortcomings and customers complaints

Some of the numbers highlight the degree to which individual homes in the U.S. are becoming miniature power plants. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, small-scale solar installations – primarily residential – grew more than fivefold between 2014 and 2022. What was once the province of climate advocates and early adopters became more mainstream owing to falling costs, government incentives, and a growing awareness of climate change.

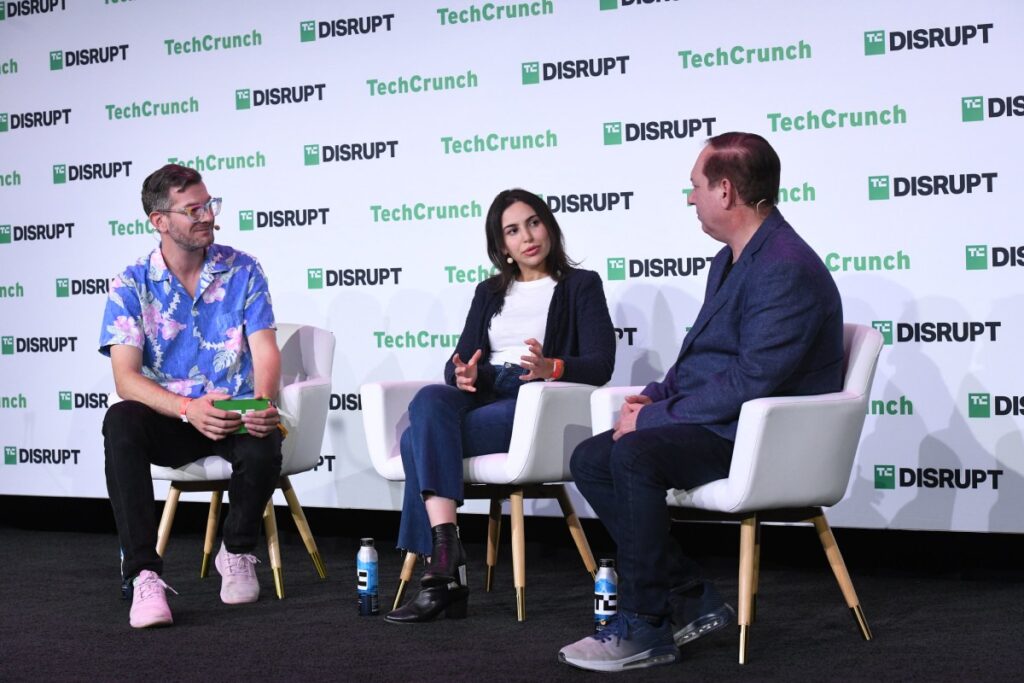

Techcrunch event

San Francisco

|

October 27-29, 2025

Each solar installation adds another node to an expanding network of interconnected devices, each one contributing to energy independence but also becoming a potential entry point for someone with malicious intent.

When pressed about his company’s security standards, Showalter acknowledges its shortcomings, but he also deflects. “This is not an EG4 problem,” he says. “This is an industry-wide problem.” Over a Zoom call and later, in this editor’s inbox, he produces a 14-page report cataloguing 88 solar energy vulnerability disclosures across commercial and residential applications since 2019.

Not all of his customers – some of whom took to Reddit to complain – are sympathetic, particularly given that CISA’s advisory revealed fundamental design flaws: communication between monitoring applications and inverters that occurred in unencrypted plain text, firmware updates that lacked integrity checks, and rudimentary authentication procedures.

“These were fundamental security lapses,” says one customer of the company, who asked to speak anonymously. “Adding insult to injury,” continues this individual, “EG4 didn’t even bother to notify me or offer suggested mitigations.”

Asked why EG4 didn’t alert customers straightaway when CISA reached out to the company, Showalter calls it a “live and learn” moment.

“Because we’re so close [to addressing CISA’s concerns] and it’s such a positive relationship with CISA, we were going to get to the ‘done’ button, and then advise people, so we’re not in the middle of the cake being baked,” says Showalter.

TechCrunch reached out to CISA earlier this week for more information; the agency has not responded. In its advisory about EG4, CISA states that “no known public exploitation specifically targeting these vulnerabilities has been reported to CISA at this time.”

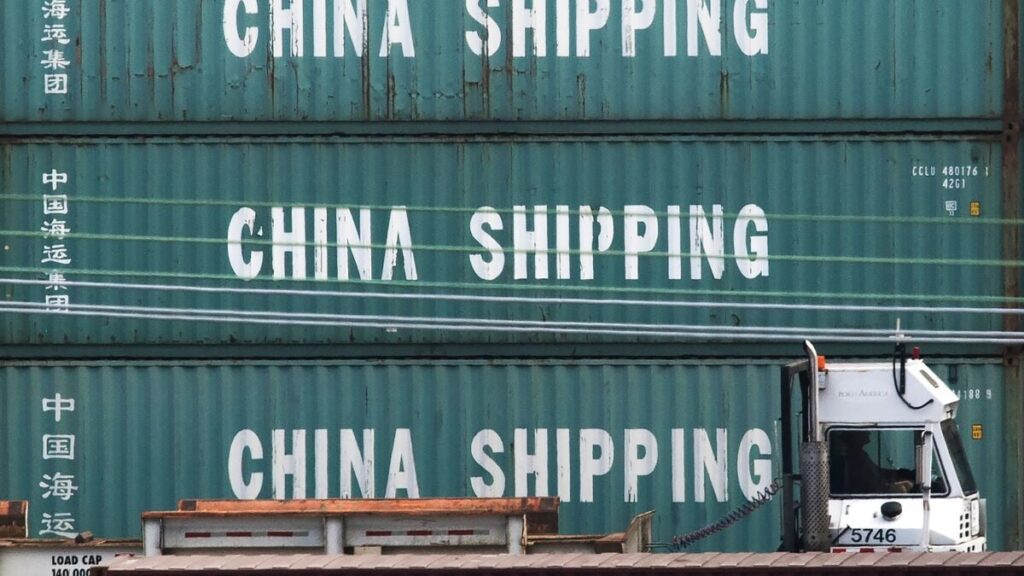

Connections to China spark security concerns

While unrelated, the timing of EG4’s public relations crisis coincides with broader anxieties about the supply chain security of renewable energy equipment.

Earlier this year, U.S. energy officials reportedly began reassessing risks posed by devices made in China after discovering unexplained communication equipment inside some inverters and batteries. According to a Reuters investigation, undocumented cellular radios and other communication devices were found in equipment from multiple Chinese suppliers – components that hadn’t appeared on official hardware lists.

This reported discovery carries particular weight given China’s dominance in solar manufacturing. That same Reuters story noted that Huawei is the world’s largest supplier of inverters, accounting for 29% of shipments globally in 2022, followed by Chinese peers Sungrow and Ginlong Solis. Some 200 GW of European solar power capacity is linked to inverters made in China, which is roughly equivalent to more than 200 nuclear power plants.

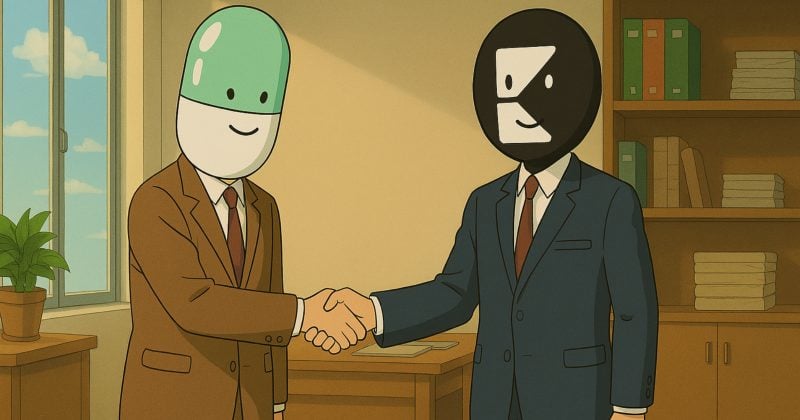

The geopolitical implications haven’t escaped notice. Lithuania last year passed a law blocking remote Chinese access to solar, wind and battery installations above 100 kilowatts, effectively restricting the use of Chinese inverters. Showalter says his company is responding to customer concerns by similarly starting to move away from Chinese suppliers entirely and toward components made by companies elsewhere, including in Germany.

But the vulnerabilities CISA described in EG4’s systems raise questions that extend beyond any single company’s practices or where it sources its components. The U.S. standards agency NIST warns that “if you remotely control a large enough number of home solar inverters, and do something nefarious at once, that could have catastrophic implications to the grid for a prolonged period of time.”

The good news (if there is any), is that while theoretically possible, this scenario faces a lot of practical limitations.

Pascale, who works with utility-scale solar installations, notes that residential inverters serve primarily two functions: converting power from direct to alternating current, and facilitating the connection back to the grid. A mass attack would require compromising vast numbers of individual homes simultaneously. (Such attacks are not impossible but are more likely to involve targeting the manufacturers themselves, some of which have remote access to their customers’ solar inverters, as evidenced by security researchers last year.)

The regulatory framework that governs larger installations does not right now extend to residential systems. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation’s Critical Infrastructure Protection standards currently apply only to larger facilities producing 75 megawatts or more, like solar farms.

Because residential installations fall so far below these thresholds, they operate in a regulatory gray zone where cybersecurity standards remain suggestions rather than requirements.

But the end result is that the security of thousands of small installations depends largely on the discretion of individual manufacturers that are operating in a regulatory vacuum.

On the issue of unencrypted data transmission, for example, which is one reason EG4 received that slap on the hand from CISA, Pascale notes that in utility-scale operational environments, plain text transmission is common and sometimes encouraged for network monitoring purposes.

“When you look at encryption in an enterprise environment, it is not allowed,” he explains. “But when you look at an operational environment, most things are transmitted in plain text.”

The real concern isn’t an immediate threat to individual homeowners. Instead it ties to the aggregate vulnerability of a rapidly expanding network. As the energy grid becomes increasingly distributed, with power flowing from millions of small sources rather than dozens of large ones, the attack surface expands exponentially. Each inverter represents a potential pressure point in a system that was never designed to accommodate this level of complexity.

Showalter has embraced CISA’s intervention as what he calls a “trust upgrade” – an opportunity to differentiate his company in a crowded market. He says that since June, EG4 has worked with the agency to address the identified vulnerabilities, reducing an initial list of ten concerns to three remaining items that the company expects to resolve by October. The process has involved updating firmware transmission protocols, implementing additional identity verification for technical support calls, and redesigning authentication procedures.

But for customers like the anonymous EG4 customer who spoke with frustration about the company’s response, the episode highlights the odd position that solar adopters find themselves in. EG4’s customers had purchased what they understood to be climate-friendly tech, only to discover they’d become unwitting participants in a knotty cybersecurity landscape that few seem to fully comprehend.